The Price of our Love

- September 23, 2021

- Hyab Yohannes

- 12 Comments

- Love and Family

-

By Hyab T. Yohannes

Our story began more than a decade ago, when we were introduced to each other through family friends. Our hometowns in Eritrea are roughly 20 kilometres apart, but our hearts and affinities have always been close, and always getting closer. Our families knew one another very well before we embarked on our improbable journey, but that was back in Eritrea. We now live thousands of kilometres away from where we were born and where our love story began. The first loss we suffered as a couple was a sense of belonging to a place we can call ‘home’, and a situatedness in a community.

I left Eritrea in 2011, fearing for my life and my future. Back then, I was a young graduate who was curious about the politics and poetics of life in Eritrea but I felt that I could not live in dignity and freedom in my home country, so went elsewhere in search of safety and a better future. At that time, Tsega was at school and not fully aware of what was happening in my life.

The decision to leave Eritrea was the biggest I had made at the time, and I did not share it fully with anybody until I had safely exited the country. It was definitely a matter of risking my own life in the hope of finding it elsewhere. After leaving Eritrea I survived bullets fired to kill me, arbitrary detention, and traffickers who wished to exploit me for ransom or organ harvesting. Sometimes, I prefer not to remember these moments of despair because they remind me of the many relatives, friends, and strangers I met who did not survive, or who have vanished without trace.

Worst of all, the decision to leave Eritrea has put up a permanent physical barrier between our parents and us. It has been more than a decade since I lost touch physically with my parents. Right now my father is frail and critically ill, but I cannot even touch his hands and bid him goodbye in his dying moments because returning to Eritrea would put my life in jeopardy. Likewise, my mother is growing weaker by the day. Will it become possible to see our parents again? I dearly hope so, but it is likely that I may never see my parents again. The same is true of my parents-in-law.

And what does the impossibility of meeting our parents have to do with our love story? Well, it all relates to situatedness in place, time, and culture, and most importantly, it is about the assertion of an ontology of life within realms of instinctual desires and who we are as humans. To find meaning in life, one has to live a life worthy of living, or one that is grounded in the aspirations, possibilities, and human finitudes of the bearer. The right to live with loved ones is, I believe, one of the fundamental tenets of a life worth living. Unfortunately, this basic filial right remains an impossibility for us. We are and have been living on the threshold of an orphanage, and this feeling of permanent loss and sense of emptiness is the second loss we have suffered as a couple.

The third loss has been the Home Office’s constant rejection of our application for a right to family reunion. I came to the UK under the Gateway Protection Programme in October 2015 and after arrival, my primary goal was to bring my wife to safety. At the time, she was living in Sudan, constantly worried about the prospect of being rounded up and deported back to Eritrea, or abducted by refugee traffickers. With the intention of avoiding this calamity, I completed a family reunion application with assistance from the British Red Cross to bring my wife to the UK. In the process, we both disclosed every single shred of information about our lives with integrity and honesty to the Home Office, in the hope of fulfilling our right to a family life, only for the entry clearance officer to declare:

You have not provided satisfactory evidence with this application that you are Tsega Eman Zerehannes. A Certificate of Marriage has been provided with this application. I note that this document is of a format easily produced locally at low cost… I am not satisfied therefore that a married (sic) has taken place as claimed nor that you are Tsega Eman Zerehannes.

For anyone who is familiar with the family reunion process in the UK, let me make it clear that we not only provided our certificate of marriage but also a whole range of private and public evidence of who we are. Among many other things, we submitted Tsega’s birth certificate, photos, hundreds of private WhatsApp messages, financial transactions, and witness statements provided by people who knew we were married. All of that, however, was deemed to not be credible as evidence, and our attempt to reunite was refused. The only thing we could do was to appeal against the Home Office’s decision and wait for the appeal hearing for months if not years. The damage to our dignity inflicted on us by the Home Office’s decision was enormous. We felt that we were effectively classed untrustworthy, and our relationship rendered disposable.

Almost a year later, my wife was kidnapped by traffickers from Khartoum. She and her younger brother, along with some friends, were found in a military prison in southern Egypt after almost a week—they had been arrested by Egyptian border security before they could be sent to torture camps in the desert, where they would have been tortured for ransom extortion and organ trafficking. This was shocking to learn, when I was in the middle of writing my MA dissertation at SOAS University of London, but having lived through years of difficult experiences and successive ordeals, I knew that I needed to just stay calm and do my best to help my wife.

Although the possibility of a reunion seemed uncertain after Tsega’s detention, our families, friends, colleagues, and even strangers stood with us all the way. When Tsega was stuck in unbearable conditions in a detention centre in Egypt, I would call friends and strangers for help, and my wife would receive immediate assistance to meet her basic needs. She would not have survived if not for the help of refugee community outreach services and the prison guards who provided her with food, water, and other basic needs. As an act of solidarity, former colleagues and community members in Cairo travelled thousands of kilometres to visit her in prison in Aswan in southern Egypt. I still remember the consoling words of a human trafficking survivor who I had assisted previously, and who later became a friend: ‘I survived certain death in Sinai because of you, and I will not allow your wife to starve while I am still in Egypt. I will travel thousands of kilometres every week to Aswan to bring her food and water.’ These acts of kindness kept Tsega and me hopeful.

Five months later, friends and former colleagues managed to assist my wife to return to Sudan, where she had a residence permit as a refugee. This was a turning point. Obviously, during the almost five months of detention, my wife had been subjected to enormous physical and mental stress, all of which could have been avoided if the Home Office had not refused our family reunion application. Despite the hurdles, borders, and unfeeling immigration policies, however, we held on to a kernel of hope that one day, we would be reunited and start a family life together in a safe place. Thankfully, never once were we forced to face these challenges on our own.

When Tsega returned to Sudan, I applied for an urgent appeal hearing of our family reunion application at the immigration court. Luckily, it was successful, and we were granted a hearing date a few days after my wife got back to Sudan. I then faced the long task of preparing all the relevant documents myself. Unsurprisingly, the immigration court dismissed the Home Office’s claims that our testimony was not credible and that our documents were fraudulent, and granted my wife entry clearance. Our unheard truthfulness and honesty had won over the Home Office’s culture of disbelief! I say this not as a judgement of the Home Office’s credibility and institutional relevance, but as a lived experience my wife and I endured, and to this day we reject violent laws, borders, and orders.

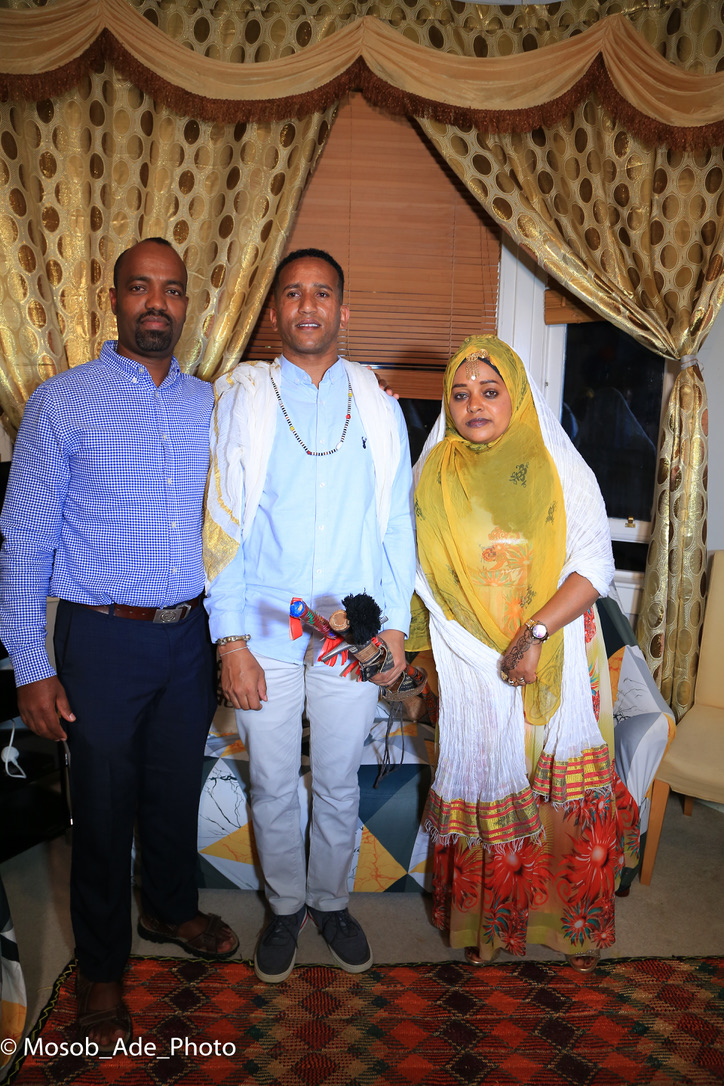

On 30 August 2021, we celebrated our greatest adventure and the happiest movement of our life. Although we had been legally married before, we chose to celebrate a religious and customary wedding party with our close friends, relatives, and new families, and although we were not able to invite our parents, we have dear friends and families here too. Friends, relatives, colleagues, and my university supervisors filled the emptiness, and I cannot thank them enough because words cannot do justice to their kindness, warmth, and presence.

Our love story has been necessarily built in the shadows cast by permanent losses and the resulting emptiness, and we denounce the barriers that prevent every life from being worth living. Nevertheless, the losses we have suffered have brought us even closer together, and we now feel that we have started a family of our own in the UK. We hope that our roots here will one day connect to our cradle in our home country, and enable our present-day to reconcile with our past.

Note: This story is dedicated to the families, friends, colleagues, and strangers who made our wedding party a day to remember. We will forever be grateful for your company, gifts, and endless warm wishes.

Wishing you both love and every happiness together. Thank you for sharing your painful story.

Thank you for your warm wishes, Liza.

Indeed very sad story with incredibly wonderful ending Mr. Hyab. I feel the pain you guys have gone through and wish you all the best in your future life as you build your family together.

Thank you, Nawd.

Warm wishes!

Powerful testimony, Hyab. Difficulty times and challenges have passed now, congratulations. Many blessings to you and Tsega

Thanks for being the best man at our wedding, Zeraslasie.

You stared death, in the face you were both tested to the limits, so many took your journey and walk the walk you both walked , but never made it to the other side.

To the victims of the Sinai , the Sahara desert, the Mediterranean Sea, or the black sea in Turkey, I say may their souls rest in peace.

To you both, I say a million congratulations. You are given second chance in life – a new beginning,

a blessed future. Your past difficulties, straggles and hurdles and the life threatening experiences that you had will only make you stronger, more appropriateve of everyday of every minute for the rest of your life. The future is already looking beautiful. You both deserve every happiness that the world has to offer.

I agree with every single word you said here, Ghergishu. Lest we forget the thousands who perished without a trace in the lifeless deserts, treacherous waters, and torture camps. May their souls rest in peace.

This true testimony is written so well and depicts the plights of hundreds if not thousands of young Eritreans who are taking perilous journeys to escape modern slavery in their home country. It is impressive how effectively the hard facts are establish which are deliberately ignored as fales accounts by governments all over the world. I salute you for telling us your personal life experiences in a bide to shine the truth and hope it will help hardened hearts to change.

We are all humbled and grateful to be part of your big day! It was truly amazing,colourful and multicultural. The despair and sadness is all over now. Hope has prevailed you and your wife.

Your thoughtsness and amazing writing is a gift and we will treasure always.

We are very appreciative and grateful for your presence, gifts and warm wishes, Abrehe. As you said, we wish the muted voices and unheard stories of the exceptionalised refugees find their way to the psyche of our collective political unconsciousness.

A happy ending to such needless suffering at the hands of bureaucracy. Thank you for sharing this Hyab-perhaps stories such as yours will bring about change. All the very best to you and Tsega.

Best wishes,

Ann

Thank you, Ann.